by Josh Sewell

|

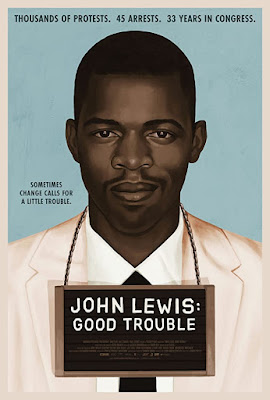

| Courtesy of Magnolia |

Our country lost a hero last weekend when Rep. John Lewis, respected legislator and icon of the Civil Rights movement, died following his battle with pancreatic cancer. In a bittersweet twist of fate, a documentary about his life, John Lewis: Good Trouble, hit VOD just a couple of weeks earlier. As a result, what was intended to be a celebration of Lewis’ life and accomplishments turned out to be a poignant eulogy – much of it in his own words.

Using interviews and rare archival footage, director Dawn Porter takes viewers through Lewis’ 60-plus years of social activism and legislative action. He recounts his involvement with the Freedom Riders and sit-ins at lunch counters; the brutal beating that nearly killed him while protesting for voting rights in Selma; and speaking alongside Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington in 1963.

As powerful as these stories are, especially coming from Lewis himself, they’ve been chronicled elsewhere (including his own graphic novel series “March,” a must-own for all young adults). What makes Good Trouble particularly compelling are the moments that recount his lesser-reported achievements, which casual viewers might not know about. In addition to his devotion to civil rights and access to the voting booth, he also fought hard for common sense gun laws, health-care reform and immigration.

Through recent interviews with Lewis, his siblings, Congressional colleagues and others close to him, Porter explores several facets of a great man’s life. Those include his childhood experiences, his proud family, his (sometimes contentious) relationships with other Civil Rights leaders, his dedication to equality and how that inspired new generations of public servants.

Although Good Trouble is a fairly standard doc with lots of talking heads and news clips, Porter makes a couple of narrative choices that keep it from feeling too run-of-the-mill. The first is her perceptive decision to juggle the chronology of events, going back and forth from present day to decades earlier.

The choice illustrates in vivid terms that Lewis’ fight didn’t end in the 1960s after the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Many of the issues he passionately advocated for are still important and unresolved today. That’s especially true concerning voting rights, which suffered a massive blow when the Supreme Court invalidated key portions of the Voting Rights Act in 2013.

The supposed reasoning was those provisions were no longer needed since the country wasn’t as racist as it was in 1965 when the act was signed. However, the film argues such justification proved to be erroneous considering the restrictions placed on voting in the seven years since the court’s decision.

The other compelling narrative choice is Porter’s idea to project footage pivotal moments of Lewis’ life and career – some of which he’d never seen – onto a screen and capture his thoughts as he watches them. Many scenes establish that Lewis often resorted to a few tried and true anecdotes when talking to crowds and media figures about his role in history. But when he watches the projected footage, it frequently leads to fascinating, unrehearsed observations.

These moments are stunning in how they prove 1960s news reports often mirror today’s headlines. The biggest difference is that Lewis’ opponents and critics have learned to couch their blunt language in more socially acceptable phrases – although some might say even that veneer has been stripped away in recent years.

While the subject matter in Good Trouble is certainly heavy and tough to watch at times, Porter’s film isn’t a slog through misery. It also conveys other important aspects of Lewis’ life: chiefly, his charismatic nature and warm sense of humor.

In one interview, a colleague describes the exhausting process of walking through an airport with him. He explains that he never knew how long it would take to reach the gate or the exit because Lewis was constantly being greeted by admirers, and he strived to have genuine conversations with all of them.

In another segment, we see him teasing a young staffer, complaining that he’s not helping an old man climb wet stairs and pretending to slip. Then the devout Lewis jokes that he’s “more baptized” because he was fully immersed in a river while his Methodist colleague merely had a few drops of water splashed on his head. Southerners will immediately recognize his brand of good-natured ribbing.

But the moment that made me smile the most is when another Lewis associate remembers celebrating his birthday. Everyone in the office was on a cake-induced sugar high when Pharell Williams’ “Happy” started blasting though the speakers. Lewis started dancing, so someone captured it on video and posted it on social media. Cut to a few hours later and the clip went viral, making national headlines during a time when people desperately needed some good news.

In today’s insanely polarized political climate, widely revered elected officials are rare. Lewis was the uncommon figure who transcended labels and was (aside from the most ultra-conservative of detractors) respected for both his words and his deeds. “Good Trouble,” while not revolutionizing the documentary form, captures that heroic goodwill at a time when our country needs it most.

John Lewis may be gone, but his directive to “never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble” lives on.

John Lewis: Good Trouble is rated PG for thematic material including some racial epithets/violence, and for smoking. Now available on VOD.

Grade: B+

Using interviews and rare archival footage, director Dawn Porter takes viewers through Lewis’ 60-plus years of social activism and legislative action. He recounts his involvement with the Freedom Riders and sit-ins at lunch counters; the brutal beating that nearly killed him while protesting for voting rights in Selma; and speaking alongside Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington in 1963.

As powerful as these stories are, especially coming from Lewis himself, they’ve been chronicled elsewhere (including his own graphic novel series “March,” a must-own for all young adults). What makes Good Trouble particularly compelling are the moments that recount his lesser-reported achievements, which casual viewers might not know about. In addition to his devotion to civil rights and access to the voting booth, he also fought hard for common sense gun laws, health-care reform and immigration.

Through recent interviews with Lewis, his siblings, Congressional colleagues and others close to him, Porter explores several facets of a great man’s life. Those include his childhood experiences, his proud family, his (sometimes contentious) relationships with other Civil Rights leaders, his dedication to equality and how that inspired new generations of public servants.

Although Good Trouble is a fairly standard doc with lots of talking heads and news clips, Porter makes a couple of narrative choices that keep it from feeling too run-of-the-mill. The first is her perceptive decision to juggle the chronology of events, going back and forth from present day to decades earlier.

The choice illustrates in vivid terms that Lewis’ fight didn’t end in the 1960s after the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Many of the issues he passionately advocated for are still important and unresolved today. That’s especially true concerning voting rights, which suffered a massive blow when the Supreme Court invalidated key portions of the Voting Rights Act in 2013.

The supposed reasoning was those provisions were no longer needed since the country wasn’t as racist as it was in 1965 when the act was signed. However, the film argues such justification proved to be erroneous considering the restrictions placed on voting in the seven years since the court’s decision.

The other compelling narrative choice is Porter’s idea to project footage pivotal moments of Lewis’ life and career – some of which he’d never seen – onto a screen and capture his thoughts as he watches them. Many scenes establish that Lewis often resorted to a few tried and true anecdotes when talking to crowds and media figures about his role in history. But when he watches the projected footage, it frequently leads to fascinating, unrehearsed observations.

These moments are stunning in how they prove 1960s news reports often mirror today’s headlines. The biggest difference is that Lewis’ opponents and critics have learned to couch their blunt language in more socially acceptable phrases – although some might say even that veneer has been stripped away in recent years.

While the subject matter in Good Trouble is certainly heavy and tough to watch at times, Porter’s film isn’t a slog through misery. It also conveys other important aspects of Lewis’ life: chiefly, his charismatic nature and warm sense of humor.

In one interview, a colleague describes the exhausting process of walking through an airport with him. He explains that he never knew how long it would take to reach the gate or the exit because Lewis was constantly being greeted by admirers, and he strived to have genuine conversations with all of them.

In another segment, we see him teasing a young staffer, complaining that he’s not helping an old man climb wet stairs and pretending to slip. Then the devout Lewis jokes that he’s “more baptized” because he was fully immersed in a river while his Methodist colleague merely had a few drops of water splashed on his head. Southerners will immediately recognize his brand of good-natured ribbing.

But the moment that made me smile the most is when another Lewis associate remembers celebrating his birthday. Everyone in the office was on a cake-induced sugar high when Pharell Williams’ “Happy” started blasting though the speakers. Lewis started dancing, so someone captured it on video and posted it on social media. Cut to a few hours later and the clip went viral, making national headlines during a time when people desperately needed some good news.

In today’s insanely polarized political climate, widely revered elected officials are rare. Lewis was the uncommon figure who transcended labels and was (aside from the most ultra-conservative of detractors) respected for both his words and his deeds. “Good Trouble,” while not revolutionizing the documentary form, captures that heroic goodwill at a time when our country needs it most.

John Lewis may be gone, but his directive to “never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble” lives on.

John Lewis: Good Trouble is rated PG for thematic material including some racial epithets/violence, and for smoking. Now available on VOD.

Grade: B+

Comments

Post a Comment